“I am the first to acknowledge that without the help of others, there was no way I could have practiced painting, but I had to make the effort, I had to continuously struggle to attract attention. My experience tells me that it does not matter how physically challenged a person is, one always has the capacity to demonstrate how useful one can be to society. Providence has a way of bringing help to people who fight without giving up.” – Joel Acheampong.

In our part of the world, physically challenged people are considered disabled and many among them consider themselves as such. Most of them are reduced to begging for a living rather than having the opportunity to apply their talents to earn a living.

It is therefore heartening to hear of a physically challenged person doing something spectacular. One cannot but want to know more.

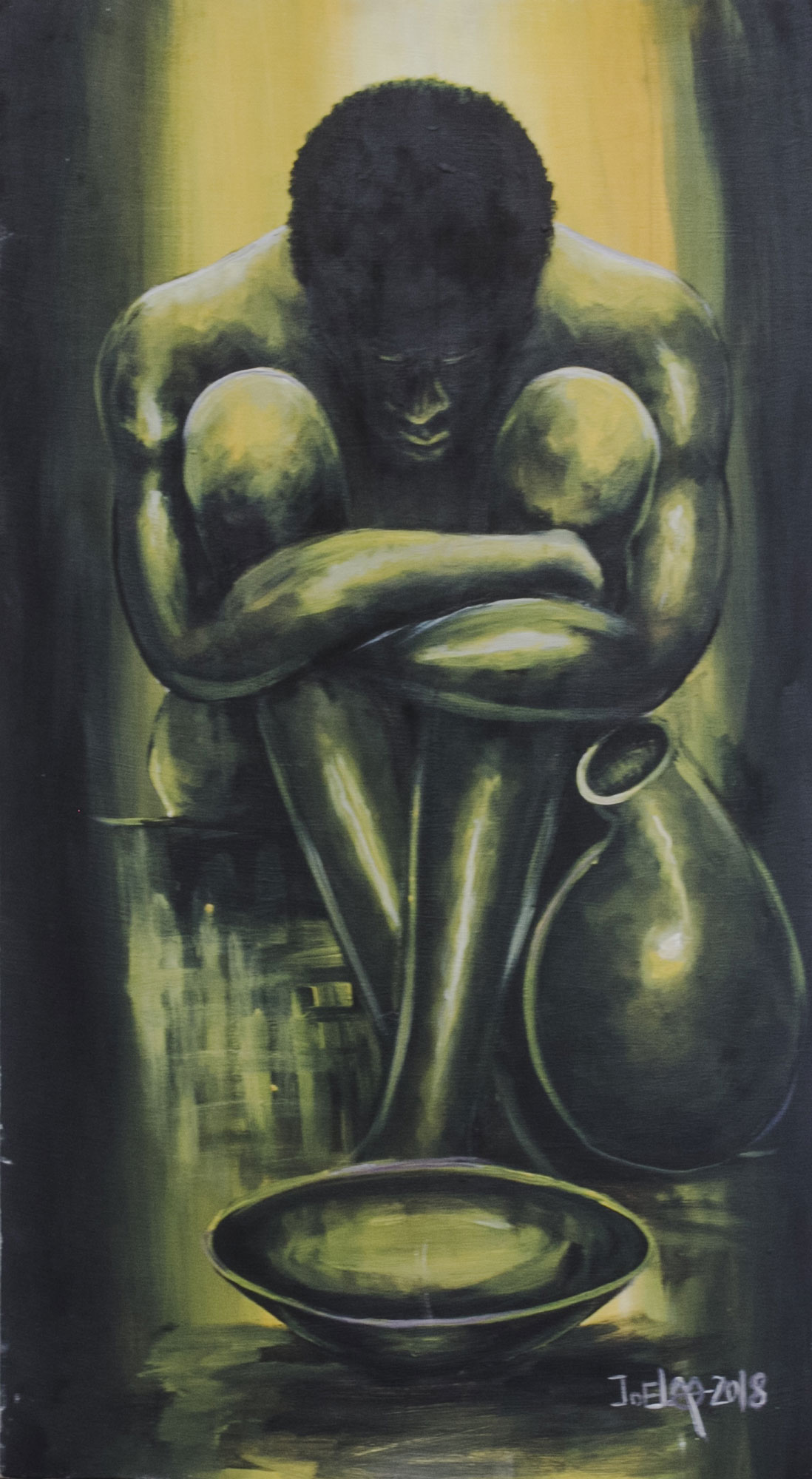

Joel, we were told is paralyzed in both arms and legs. He has to be lifted and placed in his wheelchair. He is unable to wheel himself around except when using a motorized chair. Joel indeed doesn’t have enough strength in either arm to hold a pencil and yet he paints. How? Well, he paints with his mouth!

We drove down from Accra to where Joel lives, spending about an hour and stopped right in front of Tom’s Gallery and Tea Shop. There, we spotted Joel.

When we met him, we kept the introductions short. NOVICA’s national representative was introduced to Joel and discussed NOVICA and what it does. He explained that NOVICA Ghana had heard about him and had the blessing of our head office to list Joel as one of NOVICA’s artisans. He told Joel that as part of the process we were visiting to learn more about him and his works. In short, we wanted to write his story for the world to know him and his works. After introducing the NOVICA team to Joel, he agreed to grant us an interview.

“It is a long story.” He said with a sigh after I’d told him we wanted to hear the full story.

Joel was born at Koradaso in Kumasi, Ghana, some forty-four years ago. He remembers going to kindergarten as a normal healthy child. He loved to play around with his friends and was fascinated with colors and loved to see colors on paper. The change came rather suddenly. One moment he was playing and laughing, the next moment he was ill and receiving an injection purported to heal. Then, he was bedridden. He began to lose the use of his limbs. After several attempts at being healed at all manner of health facilities, including prayer camps, his parents gave up and hid him from the public. He had no friends, he no longer played and he no longer used crayons to create art.

“I must have been about eight years old when my parents divorced.” He told me. “I was taken to a cottage in a cocoa producing area in the Obuasi District, by my mother. She farmed cocoa and assisted with trading.” He added.

From dawn to dusk, Joel was mostly alone in the cottage of only a few huts. Everyone went to the farm leaving him behind.

“In those days, I would crawl from the hut into the dusty compound clear a bit of space and create various images with charcoal on the ground with my feeble hands. My entire world was the people around me, animals, and the forest. I’d seen vehicles before but they were no longer part of my daily experience. Once in a while, an aircraft would fly overhead. There wasn’t enough strength in my arms to wave at them. In an environment such as I found myself, you can guess what I was sketching with my charcoal- mostly animals.” He smiled.

“I think we were in that cottage for about six years and then one day, my mother brought good news. She’d met a gentleman in Kumasi who was going to take me to meet a specialist to help me walk. We came to settle in my mother’s hometown, Nyankyerenease, near Kumasi. A few weeks later, I was taken to the orthopedic specialist. He was resident in Nsawam but visited Kumasi randomly to train disabled people to use various aids. On my first visit for training he tried me on crutches. It didn’t work. I was, however, able to use a four wheeled walker. I managed to use it for three years. The walker improved my movements significantly. The village had a school, and as I could now move around I made friends very quickly among the pupils.”

“How did you do it? You were not in school, were you?” I asked. His answer stunned me.

“I used to sit with some pupils when they were doing their homework and I would help them complete their art homework. Soon word went around that I could draw. Every pupil who couldn’t draw came to me for help.”

“Were you charging for your services?” I asked jokingly.

“It never occurred to me to charge. Indeed, I used to draw on the ground, now I had plenty of paper and watercolors to paint. In fact, it was through this enterprise that I went to school.”

“You were in your teens already, how were you enrolled?” I queried.

“I was not in my teens. I was past twenty already and I had no plans of going to school. One day I got a visit from a gentleman who introduced himself as an artist. He had seen some of the things I’d painted for the pupils and was impressed. He said I had talent. He brought me an art book and colored pencils for me to practice. He made friends with me and started convincing me to go to school. It was a very difficult decision to make. Firstly, I saw myself as old, at almost twenty-four. Secondly, the thought of traveling slowly every day on my walker to and from school scared me. It took quite some time before I could brave it.”

“You only attended kindergarten before your misfortune, so were you going to start from first grade?” I was curious.

“That’s another interesting part of the story. Feeling too old to join the primary school pupils, I negotiated to start in Junior High School. The Headteacher was supportive. She took me through various tests and recommended that I make a start in class six. I accepted and started schooling.”

“What were some of the challenges you faced in school?” I asked.

“There were many, but I managed to continue schooling. The biggest challenge is probably what has brought me this far.” He paused, looking pensive. I waited patiently as he resumed speaking.

“When I started schooling, I was writing and drawing using both hands together, on account of my weak limbs. I couldn’t catch up with writing notes and answering questions in written assignments within the allotted time, even though I knew the answers. It was very frustrating. My progress was being slowed tremendously.”

“Did you want to give up?”

The “No!” from him was a cry. He continued.

“I used to stay up half the night writing notes. It was when I was brooding over my predicament one such night that I decided to learn to use my mouth.”

“How?” I asked.

“Sometime in 1995, my benefactor took me to the National Cultural Centre in Kumasi to meet a philanthropist who was giving out wheelchairs. Her name was Johnnie Rexton. She was also disabled. When I told her I wanted to be a professional painter, she showed excitement, because her condition was similar to mine. She told me she was also an artist and painted with her mouth. On the night, I saw myself as Johnnie and went to work immediately.”

“You mean you just decided, and presto, you were writing by the aid of your mouth?” I wanted a miracle confirmed. He laughed.

“No, it took weeks, maybe months, of practice. My first attempt was a disaster. I couldn’t hold the pen in my mouth and it fell several times. I soon found out I was using the wrong positioning. Then I got the grip. I was excited, only to encounter a more serious challenge; the dribble. I soaked the paper before I could write a few sentences. I was teaching myself so it wasn’t easy. I had to discover the techniques one after the other through experience. Eventually, I got it!”

“It was definitely a major breakthrough for you,” I said involuntarily.

“Not yet. I was too shy to use my mouth for writing at school so I continued to write with my hands at school while writing with my mouth at home. One day, I unconsciously stuck my pen in my mouth and wrote at school. Nobody noticed it so I continued, but I was cautious and hid the maneuvers from the class. It turned out that my classmates had already spotted me and had been discussing the weird behavior amongst themselves. That was when I stopped going undercover, so to speak.”

We laughed together, after which he resumed speaking.

“Since then, I have always written and painted by the aid of my mouth. I did this throughout Junior and Senior High School.**

“Senior High school?” I exclaimed.

“Yes!” He replied quickly. “Three grueling years.”

“I was admitted to the Jachie-Pramso Senior High School, but getting enrolled became a tussle. The Assistant Headmistress, (Academics) said I needed to go to a special school while the Headmaster insisted I could still make it at their school. The next thing they considered was what program I should pursue. I’d chosen General Arts because I wanted to be a lawyer, but they offered me Visual Arts.”

“Well, by now you were secured and ready to go,” I said trying to lighten his mood.

“Well, admission was sorted out, boarding and lodging was the next hurdle, and there was also the problem of traveling to and from school daily if I were enrolled as a day student.”

“How was that challenge surmounted?” I asked.

“All this time, the man who made me go to school in the first place had been part of my struggles. He secured for me accommodation at a home for the disabled. My younger brother enrolled in a primary school in the village and became my companion. He wheeled me to school in the mornings and would then run to his school, then come back for me after closing. That’s how we did the three long years.” He sighed again.

I prompted again. “Did you gain admission to the University?”

“I had good grades except in English. I needed to improve on that in order to be admitted. I had the capacity but there were other considerations. At that point, I had to make a decision. I needed a lot of help just to move around. My brother had been around me all the while, but he had his own life to lead too. I decided to call it quits at the formal level and continue studying on the job. I joined my benefactor, who is still an artist at the National Cultural Centre, as his apprentice and I started painting at his studio. We lived in the same village, so he drove me to and from work.”

“Joel, I think it’s time we spoke about this benefactor. Tell us a bit about him.” I requested.

“I’m more than glad to do so. Mr. Mark Nyanteh is a well-known artist who works for the National Cultural Center in Kumasi. He has been my guardian since my late teens. It was by his persuasion that I went to school at the ripe age of twenty-four. He was the one who secured my first wheelchair for me. He took me under his wing after school and gave me invaluable exposure. I couldn’t thank him more. I bless him every day.”

“You were painting at the National Cultural Center, so what brought you to this village?”

“Well once again, I must credit Mr. Nyanteh. At the Cultural Center, we met with a number of tourists. A number of them have been interested in my works and offered support in various forms. It was one of these tourists, Mr. Tom Yendell, who came to introduce the Mouth and Foot Painters Association to us a few years back. In due course, Tom registered me with the Association as a student member. Tom opened a vocational school in this village some ten years ago. He added the gallery and the tea shop last year. He is the one who asked me to come here. I have been here with my family since April, 2018.”

“What have been some of the brightest moments in your life?” I asked.

“Considering my condition and counting my blessings, I can tell you every moment in my life is bright.” He philosophized, smiling.

“I bless every day made by the Lord. In terms of my work as an artist, I have been recognized already by the state and given a national award. I was among the Ghanaians who were decorated by President Kuffour in 2008 with the Ghanaian National Medal.”

“How do you see the future?” I asked.

“I will continue to paint and become a full member of the Association. I dream of founding an institute where talented people will receive help to develop their talents and use them for the benefit of society. You see, I have been lucky to meeting good Samaritans who have brought me this far. Others may not be so lucky. A more sustainable system lies within formal institutions.

“I, however, encourage everybody to put in some effort regardless of their limitations. I am the first to acknowledge that without the help of others, there was no way I could have practiced painting, but I had to make the effort, I had to continuously struggle to attract the attention needed to get help and to bring exposure for my works. My experience tells me that it does not matter how physically challenged a person is, one always has the capacity to demonstrate how useful one can be to society. Providence has a way of bringing help to people who fight without giving up.”

Joel is married to beautiful, vivacious Ruth Umalyi. They met at Church and fell for each other. They have also adopted a pair of twins, Joshua and Joseph Atta Osei, from his late elder sister, and added them to his two kids, Abena Asantewa and Amma Serwaa. So, the family has seven members, including their sister, Yawa Kwayado, who helps with the four kids. All of these family members are supported by Joel, through his paintings.

Lastly, Joel commented, “I have often wondered why God preserved me, but since the demise of my beloved sister and since her lovely twins came into my care, I have ceased wondering.”

I turned away and shut my notebook as his eyes welled. There was no need to say farewell.